Research

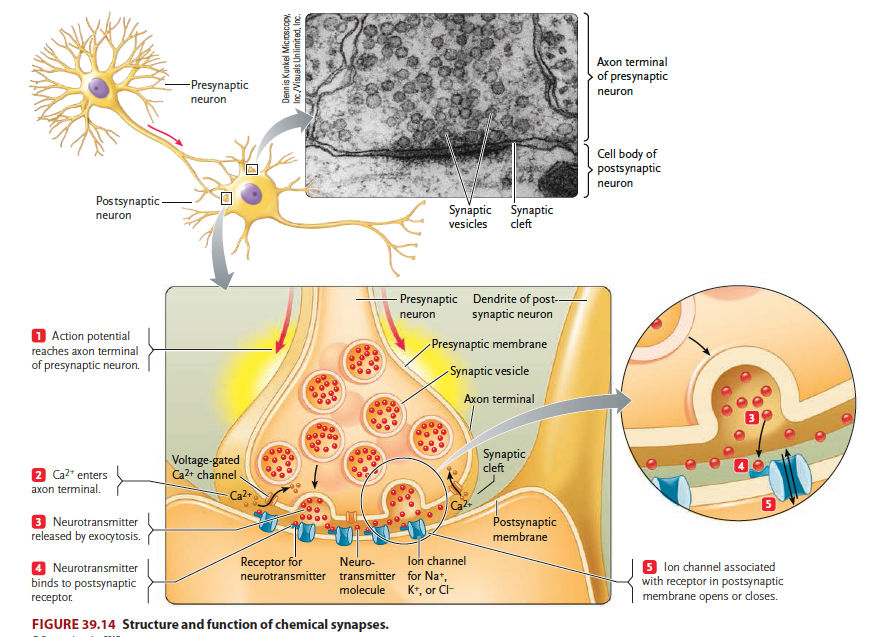

The brain contains billions of nerve cells, or neurons, which receive and integrate signals from the environment and govern the body’s responses. Neuronal activity is made possible by synapses, contact between neurons or between a neuron and a target cell such as a muscle fiber or gland cell (Figure 1). Neurotransmitter molecules are released from the presynaptic membrane and activate receptors on the postsynaptic membrane, thus establishing neuronal communication. As such, synapses are fundamental units of neural circuitry and enable complex behaviors. Research in our lab has focused on mechanisms of synapse formation and maintenance, and how their changes cause neurological disorders such as neuromuscular disorders and psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia, autism, and depression. We hope that our research will contribute to the development of novel diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for diseases associated with synaptopathy.

Adapted from Russell et al. (2016)

Figure 1. Synapses are fundamental, functional units of the nerve system, which signals are transduced from a neuron to its target neuron or cell.

The neuromuscular junction (NMJ)

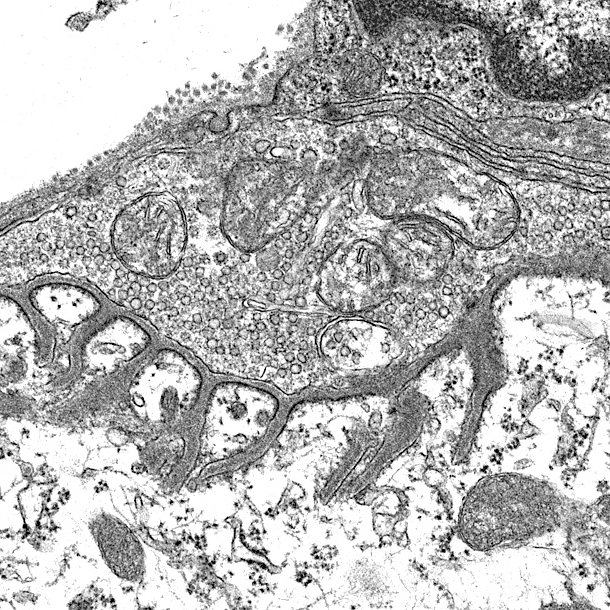

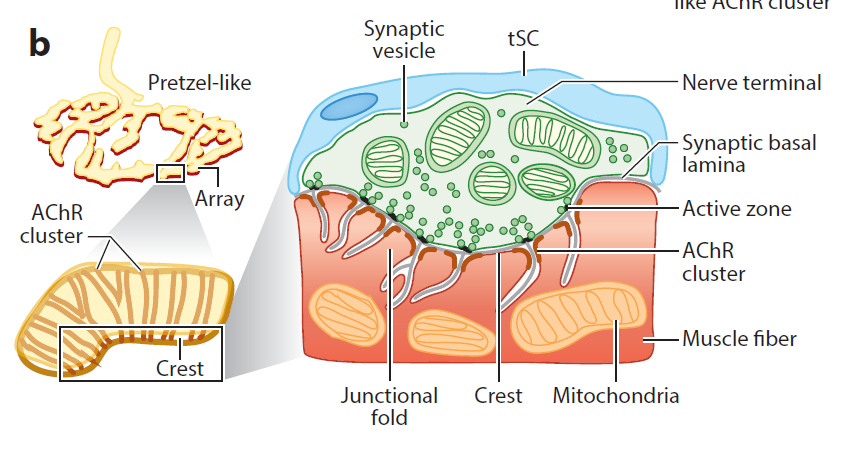

Our daily activities – get out of the bed, walk, eat, drink, and sit – requires the proper function of the NMJ, a tripartite synapse that is formed by motor nerve terminals onto muscle fibers and is covered by terminal Schwann cells (tSC). Upon the arrival of action potentials, vesicles release the neurotransmitter acetylcholine (ACh) at the active zones of presynaptic terminals. ACh binds and activates ACh receptors (AChRs) of muscle fibers; ensuing activation of muscle fibers triggers calcium release from the sarcoplastic reticulum to initiate muscle contraction.

Efficient transmission of signals from motor neurons to muscles is guaranteed by delicate structures of the NMJ. For example, the active zones are precisely aligned with the shoulders of junctional folds of muscle membranes where AChRs are packed (Figure 2). NMJs are mostly localized in the middle of muscle fibers, 1 per muscle fiber and occupy less than 0.1% of the surface area of muscle fibers.

The NMJ has fascinated neuroscientists for hundreds of years. Studies of this peripheral synapse have contributed to our understanding of the structure and function of synapses in the brain. Nevertheless, mechanisms of NMJ formation or maintenance are not well understood. NMJ deficits are known to cause or associate with neurological disorders including congenital myasthenic syndrome (CMS), myasthenia gravis (MG), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and ageing-related NMJ deficits.

Figure 2. Barik’s EM and Lei Li’s diagrams. (label pre- and post-synaptic structures)

Agrin-LRP4-MuSK signaling

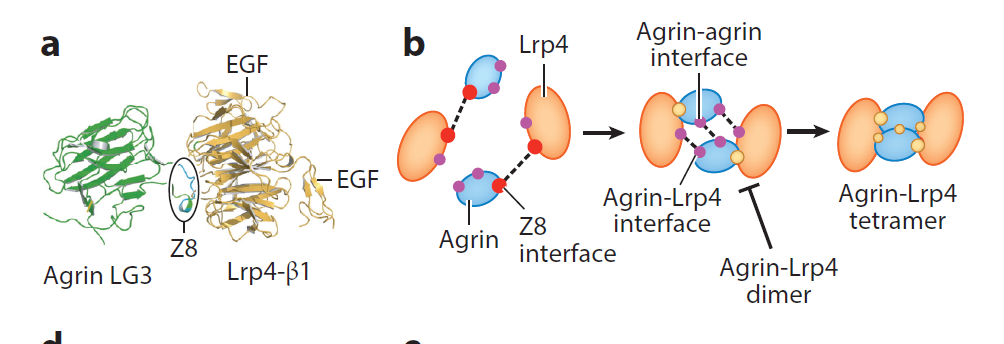

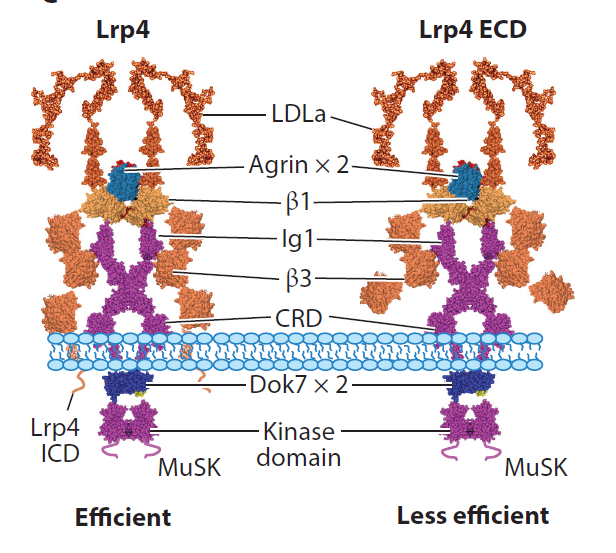

Motor neurons are known to release agrin, a proteoglycan, that activates MuSK, a transmembrane tyrosine kinase in the muscle, both of which are required for NMJ formation. However, agrin does not interact with MuSK; it was unknown how the signal was transduced from agrin to MuSK. Our lab was among the first to show that LRP4, a member of the LDL receptor family, is a receptor of agrin and can also interact with MuSK. Crystal structural analysis suggests that a tetrameric complex of two agrin and two LRP4 may be necessary for MuSK activation, likely by increasing its dimerization (Figure 3).

Figure 3. tetrameric complex. Show agrin-LRP4 crystal and Lingli He’s model.

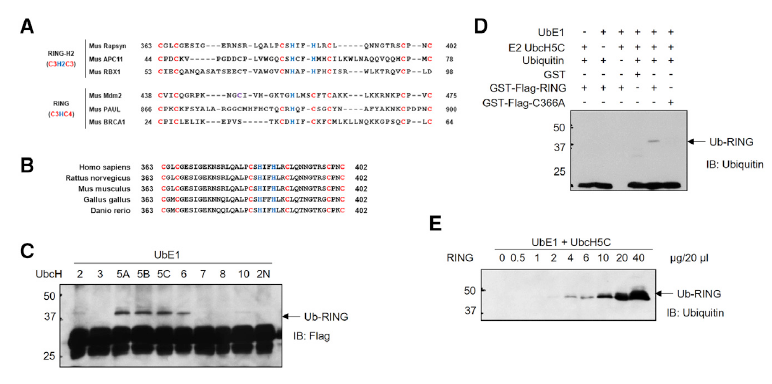

Downstream of MuSK may involve rapsyn, a classic scaffold protein that is believed to bridge AChRs to the cytoskeleton. We showed that it undergoes liquid-liquid phase separation to form membraneless condensates, which may serve as a signaling platform. In addition, rapsyn possesses E3 ligase activity that is required for NMJ formation. How rapsyn’s E3 ligase activity regulates NMJ formation remains unclear; in particular, E3 ligases may catalyze ubiquitination, sumoylation, and/or neddylation that modify proteins by conjugating ubiquitin, sumo, and Nedd8, respectively. Our recent studies of the effect of Nae1 mutation alone and in combination with rapsyn mutation support the notion that rapsyn serves as a neddylation E3 ligase in NMJ formation.

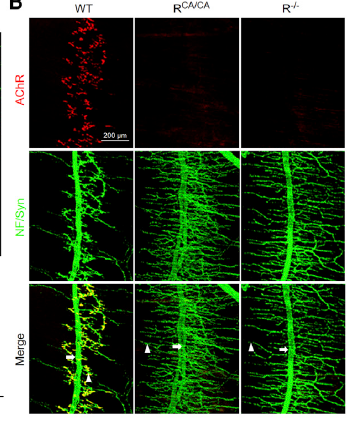

Figure 4. Show XING Guanli’s LLPS movie and Li Lei’s rapsyn enzyme assay and C366A/no NMJ.

NMJ disorders and therapeutic potentials of enhancing agrin signaling

NMJ maintenance requires agrin-LRP4-MuSK signaling. Mutations of the genes encoding key proteins in this pathway cause congenital myasthenia syndrome (CMS). We showed that rapsyn CMS mutations impair NMJ formation and maintenance by preventing liquid-liquid phase separation and neddylation. In addition, autoantibodies are detectable in patients with myasthenia gravis (MG) against MuSK. Together with physician colleagues, we detected anti-LRP4 and anti-agrin antibodies in MG patients and provided evidence that they are pathogenic by disrupting agrin signaling and to a less extent by activating complements. Patients positive with anti-LRP4 antibody appear to show more severe symptoms when they are also positive with another autoantibody (e.g., AChR or MuSK).

Enhancing agrin signaling could be beneficial to muscular disorders. We showed that increasing LRP4 levels delays NMJ aging in mice and viral expression of Dok7 in muscle cells promotes NMJ regeneration after injury.

“Wnt signaling” in NMJ formation

We demonstrate that neuromuscular junction formation is regulated by Wnt signaling. We found that MuSK interacts with Dvl, a protein necessary to initiate Wnt intracellular pathways. We showed that Dvl couples MuSK to the actin regulator PAK1, which is critical for AChR clustering. Neuromuscular junction formation requires beta-catenin, which may act by bridging AChR with the cytoskeleton and by regulating transcription.

Retrograde regulation of NMJ formation

Unlike anterograde signaling, how muscles regulate the differentiation of motor nerve terminals is less clear. In addition to postsynaptic differentiation, muscle LRP4 may regulate the development of nerve terminals. Altering beta-catenin levels in muscle cells cause deficits of not only postsynaptic but also presynaptic terminals, suggesting the existence of retrograde signal downstream of beta-catenin.

Neuregulin 1 (NRG1) and ErbB4 signaling for GABAergic transmission

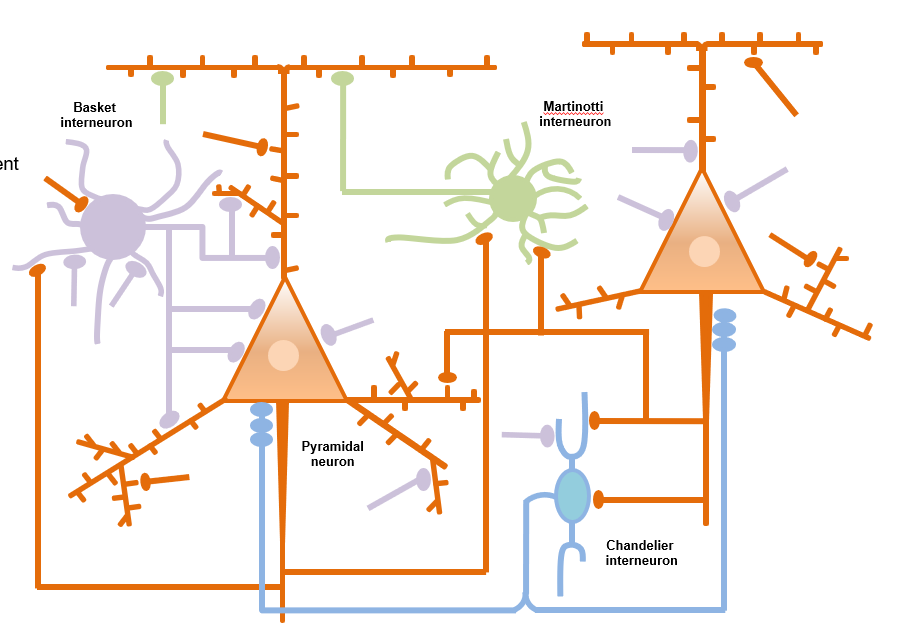

There are two main types of neurons in the brain: excitatory (also called projection or pyramidal) neurons that use glutamate as neurotransmitter and inhibitory interneurons (INs) that release GABA. Comprising 15%–20% of total neurons, INs control the excitability of projection neurons. Via feedforward and feedback inhibition, interneurons increase the computational power of cortical networks and synchronize both local and distant cortical circuits that are key to oscillatory activity. Disruptions of GABA signaling have been implicated in brain disorders including autism, depression, intellectual disability, Rett syndrome, and schizophrenia.

Neuregulin 1 (NRG1) is a trophic factor that activates ErbB4, a receptor tyrosine kinase of the EGF receptor family. We showed that NRG1-ErbB4 signaling is critical to the homeostasis of neural activity in the brain by optimizing GABAergic transmission. First, NRG1 is produced by pyramidal neurons in an activity-dependent manner. Second, it binds to ErbB4 in INs to enhance GABA release and consequently suppresses the activity of pyramidal neurons. Third, neutralizing endogenous NRG1 and inhibition or genetic ablation of ErbB4 reduces GABA transmission, suggesting a necessary role to maintain GABA activity. Fourth, functionally, acute ErbB4 inhibition by a chemogenic approach impairs cortical functions such as working memory and attention, associated with compromised synaptic plasticity and local and interregional synchrony. ErbB4 is also expressed in excitatory neurons in the spinal cord to regulate heat pain and in dopaminergic neurons in the ventral tegmental area to regulate depression-like behavior. In light of the fact that both NRG1 and ErbB4 are risk genes for psychiatric disorders including major depression and schizophrenia, our research has provided insight into pathological mechanisms of related brain disorders.

Figure 5

Studying brain functions by a risk gene approach

Many psychiatric disorders lack clear pathological hallmarks and thus are poorly understood in terms of pathophysiological mechanisms. With the advance in powerful genetic analysis, risk genes have been identified for various brain disorders. By studying mouse models of deficiency and/or de novo mutations of Erbin, TMEM108, NRG3, Caspr3, and Cullin 3 (images below, left wildtype, right Cullin 3 deficient mice), our studies reveal their physiological functions in neural development and neurotransmission and provide insight into pathophysiological mechanisms of schizophrenia, major depression and autism.